Human gastrointestinal tract

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The digestive system is the system by which ingested food is acted upon by physical and chemical means to provide the body with nutrients it can absorb and to excrete waste products; in mammals the system includes the alimentary canal extending from the mouth to the anus, and the hormones and enzymes assisting in digestion.

In an adult male human, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is approximately 5 metres (20 ft) long in a live subject, or up to 9 metres (30 ft) without the effect of muscle tone, and consists of the upper and lower GI tracts. The tract may also be divided into foregut, midgut, and hindgut, reflecting the embryological origin of each segment of the tract.[1]

The GI tract releases hormones as to help regulate the digestion process. These hormones, including gastrin, secretin, cholecystokinin, and grehlin, are mediated through either intracrine or autocrine mechanisms, indicating that the cells releasing these hormones are conserved structures throughout evolution.[2]

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Upper gastrointestinal tract

The upper gastrointestinal tract consists of the mouth cavity, salivary glands, pharynx, esophagus, diaphragm, stomach, gall bladder, bile duct, liver, and duodenum. The mouth (orbuccal cavity) contains the salivary glands; the tongue; and the teeth.

- Behind the mouth lies the pharynx which prevents food from entering the voice box and leads to a hollow muscular tube, the esophagus.

- Peristalsis takes place, which is the contraction of muscles to propel the food down the esophagus which extends through the chest and pierces the diaphragm to reach the stomach.

[edit]Lower gastrointestinal tract

The lower gastrointestinal tract comprises the most of the intestines and the anus.

- Bowel or intestine

- Small intestine, which has three parts:

- Large intestine, which has three parts:

- Cecum (the vermiform appendix is attached to the cecum).

- Colon (ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon and sigmoid flexure)

- Rectum

- Anus

[edit]Component Organs

The main organs of the digestive system are:

- Mouth

- Esophagus

- Stomach

- Small and Large intestines

- Rectum

- Anus

Other organs consist of the:

- Salivary glands

- Gallbladder

- Liver

- Pancreas

[edit]Accessory organs

Accessory organs to the alimentary canal include the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. The liver secretes bile into the small intestine via the bile duct employing the gallbladder as a reservoir. Apart from storing and concentrating bile, the gallbladder has no other specific function. The pancreas secretes an isosmotic fluid containing bicarbonate, which helps neutralize the acidic chyme, and several enzymes, including trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase, and pancreatic amylase, as well as nucleolytic enzymes (deoxyribonuclease and ribonuclease), into the small intestine. Both of these secretory organs aid in digestion.

[edit]Embryology

The gut is an endoderm-derived structure. At approximately the sixteenth day of human development, the embryo begins to fold ventrally (with the embryo's ventral surface becoming concave) in two directions: the sides of the embryo fold in on each other and the head and tail fold toward one another. The result is that a piece of the yolk sac, an endoderm-lined structure in contact with the ventral aspect of the embryo, begins to be pinched off to become the primitive gut. The yolk sac remains connected to the gut tube via the vitelline duct. Usually this structure regresses during development; in cases where it does not, it is known as Meckel's diverticulum.

During fetal life, the primitive gut can be divided into three segments: foregut, midgut, and hindgut. Although these terms often are used in reference to segments of the primitive gut, they nevertheless are used regularly to describe components of the definitive gut as well.

Each segment of the gut gives rise to specific gut and gut-related structures in later development. Components derived from the gut proper, including the stomach and colon, develop as swellings or dilatations of the primitive gut. In contrast, gut-related derivatives—that is, those structures that derive from the primitive gut, but are not part of the gut proper—in general develop as outpouchings of the primitive gut. The blood vessels supplying these structures remain constant throughout development.[3]

| part | part in adult | Gives rise to | Arterial supply |

| foregut | the pharynx, to the upper duodenum | pharynx, esophagus, stomach, upper duodenum, respiratory tract (including the lungs),liver, gallbladder, and pancreas | branches of the celiac artery |

| midgut | lower duodenum, to the first two-thirds of the transverse colon | lower duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and first two-thirds of the transverse colon | branches of the superior mesenteric artery |

| hindgut | last third of the transverse colon, to the upper part of the anal canal | last third of the transverse colon, descending colon, rectum, and upper part of the anal canal | branches of the inferior mesenteric artery |

[edit]Specialization of organs

Four organs are subject to specialization in the kingdom Animalia:[citation needed]

- The first organ is the tongue, which is only present in the phylum Chordata.

- The second organ is the esophagus. In birds, insects, and other invertebrates, the crop is an enlargement of the esophagus that is used to store food temporarily.

- The third organ is the stomach. In addition to a glandular stomach (proventriculus), birds have a muscular "stomach" called the ventriculus or "gizzard". The gizzard is used to grind up food mechanically.

- The fourth organ is the large intestine. Non-ruminant herbivores, such as rabbits, have an outpouching of the large intestine called the cecum, which aids in digestion of plant material such as cellulose.

[edit]Transit time

The time taken for food or other ingested objects to transit through the gastrointestinal tract varies depending on many factors, but roughly, it takes 2.5 to 3 hours after meal for 50% of stomach contents to empty into the intestines and total emptying of the stomach takes 4 to 5 hours. Subsequently, 50% emptying of the small intestine takes 2.5 to 3 hours. Finally, transit through the colon takes 30 to 40 hours.[4]

[edit]Pathology

There are a number of diseases and conditions affecting the gastrointestinal system, including:

- Cholera

- Colorectal cancer

- Diverticulitis

- Enteric duplication cyst

- Gastroenteritis, also known as "stomach flu"; an inflammation of the stomach and intestines

- Giardiasis

- Inflammatory bowel disease (including Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis)

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Pancreatitis

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Appendicitis

[edit]Immune function

The gastrointestinal tract also is a prominent part of the immune system.[5] The surface area of the digestive tract is estimated to be the surface area of a football field. With such a large exposure, the immune system must work hard to prevent pathogens from entering into blood and lymph.[6]

The low pH (ranging from 1 to 4) of the stomach is fatal for many microorganisms that enter it. Similarly, mucus (containing IgA antibodies) neutralizes many of these microorganisms. Other factors in the GI tract help with immune function as well, including enzymes in saliva and bile. Enzymes such as Cyp3A4, along with the antiporter activities, also are instrumental in the intestine's role of detoxification of antigens and xenobiotics, such as drugs, involved in first pass metabolism.

Health-enhancing intestinal bacteria serve to prevent the overgrowth of potentially harmful bacteria in the gut. These two types of bacteria compete for space and "food," as there are limited resources within the intestinal tract. A ratio of 80-85% beneficial to 15-20% potentially harmful bacteria generally is considered normal within the intestines. Microorganisms also are kept at bay by an extensive immune system comprising the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT).

[edit]Histology

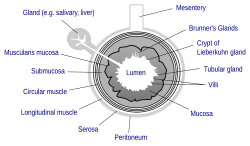

The gastrointestinal tract has a uniform general histology with some differences that reflect the specialization in functional anatomy.[7] The GI tract can be divided into four concentric layers:

- Mucosa

- Submucosa

- Muscularis externa (the external muscle layer)

- Adventitia or serosa

[edit]Mucosa

The mucosa is the innermost layer of the gastrointestinal tract that is surrounding the lumen, or space within the tube. This layer comes in direct contact with food (or bolus), and is responsible for absorption and secretion, important processes in digestion.

The mucosa can be divided into:

The mucosae are highly specialized in each organ of the gastrointestinal tract, facing a low pH in the stomach, absorbing a multitude of different substances in the small intestine, and also absorbing specific quantities of water in the large intestine. Reflecting the varying needs of these organs, the structure of the mucosa can consist of invaginations of secretory glands (e.g., gastric pits), or it can be folded in order to increase surface area (examples include

[edit]Submucosa

The submucosa consists of a dense irregular layer of connective tissue with large blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves branching into the mucosa and muscularis externa. It containsMeissner's plexus, an enteric nervous plexus, situated on the inner surface of the muscularis externa.

[edit]Muscularis externa

The muscularis externa consists of an inner circular layer and a longitudinal outer muscular layer. The circular muscle layer prevents food from traveling backward and the longitudinal layer shortens the tract. The coordinated contractions of these layers is called peristalsis and propels the bolus, or balled-up food, through the GI tract.

Between the two muscle layers are the myenteric or Auerbach's plexus.

[edit]Adventitia

The adventitia consists of several layers of epithelia.

When the adventitia is facing the mesentery or peritoneal fold, the adventitia is covered by a mesothelium supported by a thin connective tissue layer, together forming a serosa, or serous membrane.

[edit]See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Digestive system |

- Dysbiosis

- Gastrointestinal hormone

- Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary

- Major systems of the human body

[edit]Notes

- ^ lungs; Jean Hopkins, Charles William McLaughlin, Susan Johnson, Maryanna Quon Warner, David LaHart, Jill D. Wright. Human Biology and Health. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ^ Nelson RJ. 2005. Introduction to Behavioral Endocrinology. Sinauer Associates: Massachusetts. p 57.

- ^ Bruce M. Carlson (2004). Human Embryology and Developmental Biology (3rd ed.). Saint Louis: Mosby. ISBN 0-323-03649-X.

- ^ Colorado State University > Gastrointestinal Transit: How Long Does It Take? Last updated on May 27, 2006. Author: R. Bowen.

- ^ Richard Coico, Geoffrey Sunshine, Eli Benjamini (2003). Immunology: a short course. New York: Wiley-Liss. ISBN 0-471-22689-0.

- ^ Animal Physiology textbook

- ^ Abraham L. Kierszenbaum (2002). Histology and cell biology: an introduction to pathology. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 0-323-01639-1.

[edit]References

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

[edit]External links

- Anatomy atlas of the Digestive System

- Overview at Colorado State University

- Your Digestive System and How It Works at National Institutes of Health

- Normal Anatomy of Digestive Tract and anatomical abnormalities and diseases, Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NDDIC)

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

toolbox

languages

- Afrikaans

- Aragonés

- العربية

- Asturianu

- Aymar aru

- বাংলা

- Bân-lâm-gú

- Bosanski

- Български

- Català

- Česky

- Cymraeg

- Deutsch

- ދިވެހިބަސް

- Ελληνικά

- Español

- Esperanto

- Euskara

- فارسی

- Français

- Frysk

- 한국어

- हिन्दी

- Hrvatski

- Ido

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Interlingua

- Íslenska

- Italiano

- עברית

- Latina

- Latviešu

- Lietuvių

- Lingála

- Lojban

- Magyar

- Македонски

- Malti

- Nederlands

- 日本語

- Norsk (nynorsk)

- Norsk (bokmål)

- Polski

- Português

- Română

- Runa Simi

- Русский

- Саха тыла

- Shqip

- Simple English

- Slovenčina

- Slovenščina

- Српски / Srpski

- Basa Sunda

- Suomi

- Svenska

- Tagalog

- தமிழ்

- ไทย

- Türkçe

- Українська

- اردو

- Tiếng Việt

- Winaray

- ייִדיש

- Žemaitėška

- 中文

No comments:

Post a Comment